By the summer of 1920, when the final vote on the 19th Amendment took place in Nashville, Tennessee, 72 years had elapsed since the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls, New York.

By then, over 20 countries and 15 U.S. states, mostly in the West, had already recognized women’s right to vote.

American suffragists had taken dramatic and forceful steps in their fight, including massive marches, arrests for voting illegally and picketing the White House, hunger strikes, and enduring harsh treatment in prison.

Below, you’ll find a timeline detailing the efforts for the 19th Amendment and key milestones in extending voting rights to women.

1848 – The Seneca Falls Convention

At the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, led by Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, attendees adopted the Declaration of Sentiments.

This document called for equal rights for women, including the controversial demand that women should have the right to vote.

The voting rights resolution narrowly passed, thanks to the backing of Frederick Douglass, an early supporter of women’s suffrage.

1869 – Wyoming Leads with Women’s Suffrage

As the women’s rights movement grappled with the implications of the newly ratified 14th Amendment and the proposed 15th Amendment, which extended voting rights to Black men but excluded women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B.

Anthony established the National Woman Suffrage Association to advocate for a constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage.

Meanwhile, Lucy Stone and others who disagreed with Stanton and Anthony’s approach opted to pursue suffrage state by state.

The division grew deeper when Stanton and Anthony opposed the 15th Amendment, causing a rift with Frederick Douglass and alienating many Black suffragists.

Despite these tensions, Wyoming’s legislature passed the first law in the U.S. granting women suffrage in December 1869, making it the first state to allow women to vote when it joined the Union in 1890.

1872 – Arrests in New York Over Illegal Voting

In Rochester, New York, Susan B. Anthony and more than a dozen other women were arrested for illegally voting in the presidential election.

Anthony contested the charges but was fined $100, which she refused to pay.

1878 – Push for a Constitutional Amendment

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”#19thAmendment pic.twitter.com/ajrCZX9r8f

— XVIII Airborne Corps & Fort Liberty (@18airbornecorps) August 18, 2020

California Senator Aaron Sargent introduced a women’s suffrage amendment in the U.S. Senate, drafted by Stanton and Anthony.

It stated: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

This text would remain unchanged when Congress finally passed the amendment over four decades later.

1916-17: Jeanette Rankin Elected to Congress and the ‘Night of Terror’

Jeanette Rankin of Montana, previously a lobbyist for NAWSA, made history as the first woman elected to Congress. As the U.S. entered World War I, NAWSA president Carrie Chapman Catt dedicated the organization to supporting the war effort.

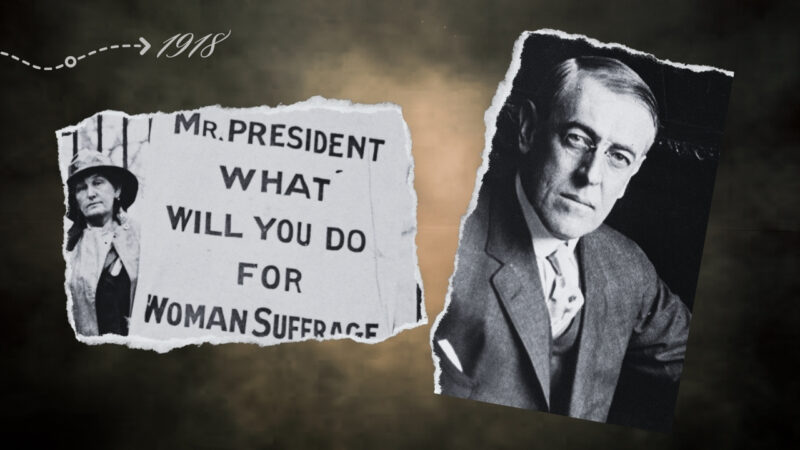

Contrarily, Alice Paul and her colleagues continued their advocacy through peaceful protests outside the White House, demanding President Wilson’s support for women’s suffrage.

Many protesters, including Paul, were arrested for obstructing sidewalk traffic and subjected to harsh treatment, leading to hunger strikes to highlight their plight.

On November 14, 1917, an infamous incident known as the “Night of Terror” occurred, where 33 women detained for picketing endured brutal treatment by guards at Virginia’s Occoquan Workhouse.

1918: President Wilson Advocates for Women’s Suffrage

In January 1918, Representative Rankin initiated a crucial debate in the House on a constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage.

The amendment passed the House but failed in the Senate. By September, President Wilson had shifted his stance, advocating for the amendment in a congressional speech.

1919: The Push for Ratification

The 19th Amendment, often referred to as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, was passed by the House on May 21, 1919, and by the Senate on June 4. It then went to the states for ratification, needing the approval of 36 states.

By the end of 1919, 11 states had ratified the amendment, but Georgia and Alabama had rejected it, influenced by anti-suffrage campaigns backed by powerful business and conservative interests. By year’s end, additional states including Arkansas, Nebraska, and Colorado had ratified it, leaving suffragists 14 states shy of their goal.

January 1920: More States Ratify

The new decade began with five more states ratifying the amendment and South Carolina rejecting it.

March 1920: One State Shy of Ratification

By March, the amendment had been ratified by 35 states, just one short of the necessary total. However, opposition remained strong, with Virginia, Maryland, and Mississippi voting against ratification.

June 1920: Setback in Delaware

Delaware’s rejection of the amendment posed a significant setback, with anti-suffrage sentiment prevailing in the few remaining states yet to vote.

Connecticut, Vermont, and Florida chose not to consider the amendment, leaving only North Carolina and Tennessee, with North Carolina expected to reject.

August 1920: Tennessee’s Decisive Vote

In a dramatic turn of events, the Tennessee legislature convened in a special session to decide the fate of the amendment.

Intense lobbying from both suffragists and their opponents marked this period, known as the “War of the Roses.”

The Tennessee Senate ratified the amendment, but the House was initially deadlocked until Representative Harry Burns, influenced by a persuasive letter from his mother, switched his vote to support suffrage. Tennessee’s ratification on August 18, 1920, achieved the required majority.

Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby certified the 19th Amendment on August 26, granting American women the right to vote.

In the subsequent presidential election, over 8 million women voted, though discriminatory practices still barred many, especially Black women, from the polls.

Despite these challenges, the literary works of Black women continued to inspire and advocate for equality and social change during this pivotal era.

1924: Native Americans Gain Citizenship

In 1924, four years following the ratification of the 19th Amendment, the Snyder Act, also known as the Indian Citizenship Act, was passed, granting U.S. citizenship to Native Americans.

However, despite this recognition, many Native American women and men were still effectively prevented from voting.

It wasn’t until 1962 that Utah became the last state to extend full voting rights to Native Americans, ending nearly four decades of disenfranchisement.

1965: The Voting Rights Act Enacted

The civil rights movement culminated in significant legislative achievements, one of which was the Voting Rights Act signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on August 6, 1965.

This landmark legislation, a result of decades of activism by Black women and men against discriminatory practices like poll taxes and literacy tests, safeguarded the voting rights of all citizens under the 14th and 15th Amendments.

1984: Mississippi Ratifies the 19th Amendment

On March 22, 1984, Mississippi became the last U.S. state to ratify the 19th Amendment.

This formal recognition came decades after the amendment had granted women across the nation the right to vote, highlighting the prolonged journey toward universal suffrage in the United States.